People love to decorate themselves. While stage actors and actresses were getting designs painted on their bodies, there were many other people getting permanent markings and proudly displaying them for all to see.

10 Bromide, Whiskey, And Cocaine

Society women of the late 1800s absolutely loved their tattoos, but they abhorred the idea of pain. In order to overcome their fear of the pricking needle, a special cocktail was taken beforehand. First, the woman took some bromide to calm her nerves. If she wanted, she could take her bromide in a stiff shot of whiskey. When she was ready, the tattoo artist (usually a woman in the high society circles) pulled out a bottle of liquid cocaine. Using a small sponge, she applied the cocaine to the area where the tattoo was to go on. This helped numb the skin and could be applied over and over again until the tattooing was complete. The tattoos were usually small and placed on the woman’s arm, where she could hide them with a long glove, if she desired. Shamrocks, hearts, and the outline of a favorite pet were common tattoo designs for women in 1899.[1]

9 Tattoos From The Great War

It was World War I, and women wanted to show their support, not only for the war but for their men as well. By 1915, it quickly became the trend for women to visit tattoo artists and have the regiment of their sweethearts tattooed onto their skin. The common spot for the tattoo was on their upper arm. Considered the “latest wrinkle,” the dedicated women of England had no qualms about showing their support and affection for the men they loved and admired.[2] Meanwhile, soldiers who were captured by the Germans were getting a different sort of tattoo. As the story went, a prisoner escaped one of the German prison camps. In an effort to quickly identify any further escaped prisoners, all captives had a hand tattooed with “Kr-Gef” plus the year of imprisonment. The letters were the German abbreviation for “war prisoner.”

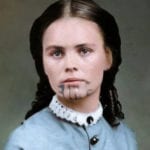

8 Tattoo Their Chins

According to Reverend Arthur Ranier of New Zealand, women had a severe problem with keeping the hem of their dresses tight around their ankles. They were cheaters at heart, and something had to be done about the situation. Back in 1908, Rev. Ranier felt that it would be best for everyone if women, upon marriage, would get a tattoo on their chins, marking them as already taken. This, he believed, would put an end to divorce, and it would stop women from leaving the home to have affairs with other men. Fortunately, not everyone was buying into this nonsense. As one newspaper asked, “By what scientific reason does the divine idiot come to the conclusion that that would stop the ‘affairs?’ ” In fact, most reports of infidelity during the early 1900s claim that the other man was just as responsible, and sometimes fully responsible, for the infidelity. A simple chin tattoo was not going to stop the passions of the heart or the loins.[3]

7 Vaccination And Bullet Scars

Ben Corday ran a little tattoo shop in Louisiana back in 1922 and was interviewed for a newspaper about his unusual trade. His insight into who got tattoos and what designs they got proves that very little has changed in the tattoo world. For example, couples would get initials tattooed on their ring fingers. Sailors were often customers and liked to get pretty girls or patriotic tattoos on their arms. Sometimes, the artist was asked to do cosmetic work and would replace a scarred eyebrow with a tattooed one instead. Corday would beautify scars, hiding them under a feminine tattoo. Vaccination scars were a big issue with women in the 1920s, and the artist stated that he would fix the vaccination marks with a tiny flower or butterfly tattoo. One tattoo trend that was unique to the times was the laurel wreath. Soldiers who returned from wars with bullet scars would get a laurel wreath around the wound to show victory over death.[4]

6 Milk And Toothpick Tattoo Removal

It was said to have been an old sailor’s trick to get rid of unwanted tattoos, but it soon became a way for criminals to try and get rid of identifying marks on their skin so as to avoid justice. According to the sea lore being bantered about in 1899, the best way to get rid of a tattoo was to use milk and a toothpick. The process was painful, according to one account. To erase the ink, one had poke the toothpick into the tattooed skin, over and over, and then let the milk soak into the skin to break up the ink. The area would scab over and then scar. Criminals who wanted to further fool the police would get a new tattoo over the scarred area so that if they were captured and questioned, the criminals could show that they were not the person they were accused of being.[5]

5 An End To Nude Women Tattoos

What is a sailor without at least one naked lady tattoo? Apparently, those naked tattoos were extremely popular in 1917, when US Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels decided that men who bore those naughty tattoos could not join the Navy. This was a huge disaster at the time because World War I was raging. Many former Navy men and old seafolk wanted to reenlist, feeling it was their civic duty and that they had valuable skills to teach the younger enlistments. In response to Secretary Daniels’s decision, the Navy League offered to help these men. The idea was to get tattoo artists to cover up their nude ladies with skirts and dresses, but Daniels would have none of it. Instead, he decided that if these older men wanted to return to the Navy, they would have to spend their own money getting their objectionable tattoos covered up.[6]

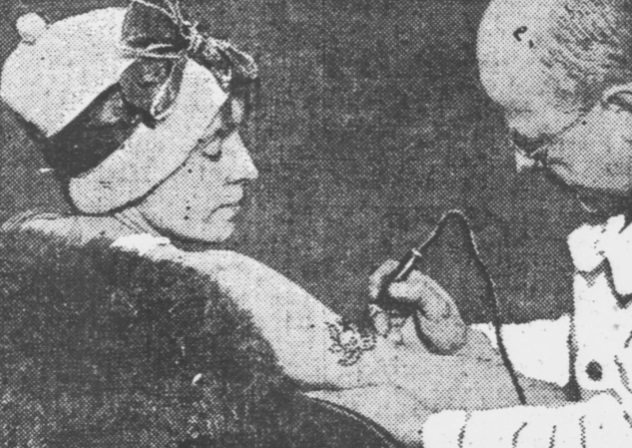

4 Permanent Complexion

Getting permanent rosy cheeks was high fashion in London, and it didn’t take long before the trend hit New York City in 1920. Women lined up to get their cheeks tattooed with healthy-looking tints. While the specialist was at it, they could also get scars blotted out and have eyebrows replaced with neat, permanent markings. Brightly tattooed lips were also very popular, and many older women felt that the permanent makeup made them look younger. All of this was made possible with the invention of the electric needle. The hand-pierced tattoos of the past were too uneven to be used for makeup, but the electric needles ensured that the needle would pierce the skin at the right depth, and new, nonpoisonous pigments gave tattoo artists a palette that went beyond blue and red.[7]

3 Identification

Sailors and seamen knew well that their tattoos could be a way for others to identify their bodies if the worst should happen. During World War I, some of the soldiers would get their names tattooed on their bodies because they knew that the identification tags handed out to them could be easily lost in the explosions that were a part of the horrifying trench experience. In one curious tale, published in 1908, a homeless man was identified sometime after his death, and it was all because of his tattoo. As the story goes, an embalmer, Mr. Oakley, had to gather up the pieces of a tramp who was run over by a train in Kansas. As Oakley looked over each remaining piece of the former man, he realized that there was no way to put the poor fellow back together for identification purposes. Luckily, however, Oakley had good eyes, and he spotted a tattoo on a piece of skin. Oakley cut and cleaned the marked skin and actually tanned it in the hopes of identifying the remains. The bits of the homeless man were then buried in the potters’ field. The tanned, tattooed skin was shown off as an oddity at first, but it didn’t take long for word to get out about the tattooed hide. One day, an elderly couple walked in to view the tattooed skin. Upon seeing it, the couple became overwrought with emotion. It was the tattoo worn by their wayward son, whom they had been searching for. The remains of their son were located in the potters’ field and returned with the couple back to California, where he could be buried in the family’s plot.[8]

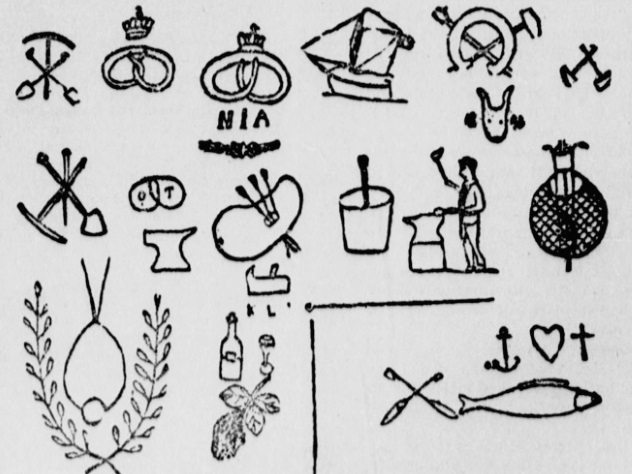

2 The Tattoos Of Anarchists

While women were getting the fleur-de-lis tattooed on their arms, anarchists were busy getting their own permanent markings. A report from 1903 claimed that many anarchists, while keeping their personal views from friends and neighbors, bore crude tattoos so that other anarchists could recognize them. More surprising is the fact that nearly all of the tattoos associated with the anarchists represented work and were not artistic in the slightest. Some of the designs were of shovels and picks. Other designs incorporated hammers and the anvil.[9] Criminologists believed that the reason the anarchist tattoos portrayed the tools of the working man was because, “As a rule, anarchists are good workers, thrifty and seldom addicted to dissipation.” Despite their good work ethics, anarchists were banned throughout Europe during that time. Their only safe havens were in England and in the United States, where they could meet up and discuss their ideas without the threat of the secret police discovering and arresting them. The anarchists were not the only secret groups being tattooed in the early 1900s. A number of tattoo artists admitted that they believed in the hushed whispers of underground societies because men would show up within a close time frame and request a certain design that was never used before.

1 The Monogrammed Dog

It wasn’t enough that sailors and society women were getting decorated with tattoos in 1899. People, with little else to do, had to take the tattoo fad a step further, so they began tattooing their dogs. The trend was to get family dogs tattooed, preferably monogrammed with the owner’s initials. This was usually done on the dog’s breast, just below its collarbone so that it was visible to all. A scrollwork design was sometimes tattooed around the monogram for a fancier look. One article stated that the “process is necessarily painful” but that the dog would patiently endure the pain for “any improvement upon himself.” While it is easy to blame the dog owners for such cruelty, we must also remember that this was a very lucrative side business for many tattoo artists, who would visit the homes of the wealthy and offer up the dog tattoos for the same price it would cost a human to get the same monogram.[10] Elizabeth, a former Pennsylvania native, recently moved to the beautiful state of Massachusetts where she is currently involved in researching early American history. She writes, and travels in her spare time.