One of the first mammals to develop saberteeth, Machaeroides were about the size of a large fox or small coyote, but due to its enlarged canines, it probably could kill larger prey than other, similarly sized predators. Machaeroides lived in the Eocene period, over 50 million years ago; it belonged to the Creodonta group, which were predatory mammals that ruled the world before the appearance of the Carnivora (the group modern day meat-eating mammals belong to). By the way, Machaeroides must not be confused with Machairodus, which was an authentic sabertooth cat, and member of the Carnivora order that replaced creodonts such as Machaeroides.

Not only meat-eaters evolved saberteeth. Uintatheres, also from the Eocene period, were large, rhinoceros-like beasts, completely vegetarian, but with a pair of monstrous looking canines. Since only male Uintatheres seem to have saberteeth, it is unlikely that they were necessary for defense against predators or for feeding; it is more likely that these saberteeth served mostly as an inter-species weapon, with male Uintatheres using them to cause serious injury to each other during fights over dominance or the right to mate. Like modern day hippos, Uintatheres surely had very thick skin, as well as an enhanced healing capacity to survive these bloody duels.

Gorgonopsids are practically unknown to the general public, although they achieved some fame among prehistoric monster fans due to their appearance in British TV show Primeval. These creatures had traits common to both mammals and reptiles, and are often seen as a “link” between the two groups. They were highly evolved predators, and most of them had saberteeth. It is likely that Gorgonopsids evolved saberteeth as a response to prey species becoming larger and developing thicker, more resistant skin. Gorgonopsids ranged in size from that of a house cat, to four or six meters long in the largest species (Leontocephalus, Inostrancevia). Some Gorgonopsids had not one, but two pairs of short, dagger-like saberteeth! In order to use them, Gorgonopsids could open their jaws to a full 90 degree angle! This made them probably the deadliest predators during the Permian period (280-250 million years ago).

Dinofelis means “terrible cat”, and is a very fitting name for this jaguar-sized feline, which roamed Africa, Asia, Europe and North America about 5-1 million years ago. Armed with short dagger-like teeth, Dinofelis is one of many true felines to develop saberteeth but it stands out because it was seemingly a specialized primate-hunter. Indeed, fossils of baboons and other primates are often found in ancient Dinofelis lairs, and some of these fossils even have puncture holes that match Dinofelis’ saberteeth perfectly. Among the primate species it hunted, were two of our hominid relatives, Australopithecus and Paranthropus; this suggests that Dinofelis played an important part in our early ancestors’ nightmares. Dinofelis went extinct due to the disappearance of forests (and many primate species) at the start of the last Ice Age.

This strange-looking beast resembled a cross between a bear and a sabertoothed tiger. It was, however, unrelated to either of them; it belonged to its own family, Barbourofelidae, and was one of the top predators in North America during the Miocene period, about 13-5 million years ago. Unlike felines, Barbourofelis was a plantigrade, meaning that it didn’t walk on its toes but on the entire sole of the foot, like bears or humans. This made it quite a bit slower than true feline sabertooths, and so probably Barbourofelis was more of an ambush hunter and rarely chased after prey. Its enormous size (as big as a lion, but much stronger) and plantigrade stance, which allowed it to stand on its hind feet like a bear, allowed Barbourofelis to wrestle large prey to the ground and hold them firmly in place while delivering a fatal bite with its 23 cm long sabers.

Nimravids were yet another group of predatory mammals that went extinct without leaving any descendants. However, they were highly succesful and numerous during the Eocene to Miocene periods, 37-5 million years ago. They looked a lot like cats, but had saberteeth and many had strange, scabbard-like flanges on their lower jaws which protected the sabers when the animal was not using them. There is fossil evidence suggesting that Nimravids were extremely vicious and dangerous animals, and that the different species killed each other in gruesome fights. For example, the skull of a small species, Nimravus, was found with a hole that matched the saberteeth of Eusmilus, a larger Nimravid from the same time and place. Amazingly, the wound seems to have healed partially, meaning that the Nimravus survived the encounter!

The ever famous “sabertooth tiger”, Smilodon was among the largest true sabertoothed cats, with the South American species reaching 500 kgs in weight! Made even more frightening by the fact that it seemingly hunted in packs (or would it be “prides”?), the largest Smilodon had 30 cm long canines and were adapted to kill large prey, from bison and horses to mammoths and ground sloths. One bite from a Smilodon was probably enough to cause massive bleeding and shock, and, if delivered to the right place, to pierce internal organs and/or sever important arteries and veins. They also had immensely strong forelimbs and enormous claws, which means they could wrestle large animals to the ground more easily than modern lions or tigers. It is even believed that Smilodon caused the extinction of other predators when it crossed to South America for the first time. The scariest thing about Smilodon? It went extinct only 10,000 years ago, meaning that modern human beings encountered these deadly cats, and probably fell prey to them once in a while.

Although it looked somewhat like a sabertooth cat, Thylacosmilus was actually a marsupial, more closely related to koalas and kangaroos than to Smilodon. It was among the top predators in South America during the Miocene, Pliocene and early Pleistocene periods. It was not as large as Smilodon- being about the size of a modern day jaguar, but its saberteeth were even more extreme. While the fangs of Smilodon reached their maximum size and then stopped growing once the cat reached adulthood, Thylacosmilus’ sabers kept growing throughout its entire life. They were so long that the roots of the canines arched over the orbits, giving the animal its characteristic arched forehead. Due to the canines being so long, Thylacosmilus (like the already mentioned Nimravids) had scabbard-like flanges on the lower jaw to protect the sabers when not in use. Thylacosmilus was slower than Smilodon and probably an ambush hunter. It was likely a deadly beast, but its long reign ended in the Pleistocene when true felines, among other predators, arrived to South America, replacing many of the native marsupial meat eaters. Among the newcomers was Smilodon, and Thylacosmilus could simply not compete with its monstrous feline counterpart and went extinct about 2 million years ago.

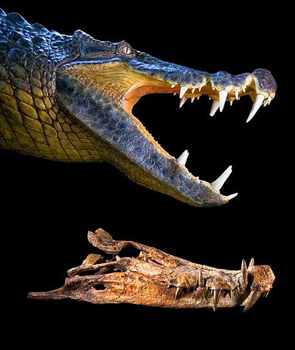

Perhaps the most monstrous-looking of all sabertoothed creatures, the recently discovered Kaprosuchus was a very large (six meter long) crocodilian with not one, but three pairs of saberteeth! One of these pairs was located in the lower jaw and when the crocodile closed its mouth, they protruded like a wild-boar’s tusks, hence its popular nickname “Boar Croc”. Unlike modern day crocodiles, Kaprosuchus was seemingly a fully terrestrial animal, and it is believed to have hunted other large terrestrial animals – including dinosaurs. It is not known if it hunted alone or in packs, since only one skull from this species has been found, but either way, it was certainly a formidable killer,which has been described as the equivalent to “a sabertoothed cat in armor”. It lived during the Cretaceous period, 95 million years ago, in what is, today, the Sahara desert.

Most sabertoothed animals have become extinct, but there is still a dangerous predator in our times that uses enlarged fangs to kill prey, and it is easily the least known and most bizarre of them all. The Burrowing Asp is a smallish snake from Africa that spends most of its time underground. It feeds on rodents, and has enlarged fangs that function basically as venomous saberteeth, protruding out of the mouth when in use. This means that the Burrowing asp can bite without even opening its mouth- which is very useful since it prevents dirt from entering the snake’s mouth during the struggle. Unlike the sabers of the previous animals, the burrowing asp’s are flexible and can be moved independently from each other, meaning that the snake can stab its prey sideways with one fang, and once it has killed its victim, it can use the movable fangs to actively manipulate the prey’s body for easier swallowing. Burrowing asp venom is moderately potent, and since the snake can bite with its mouth closed, extra care is necessary if manipulating one. Some cases of children dying after a Burrowing Asp bite are known; however, since these snakes seldom leave their underground burrows, encounters between them and humans are rare.

Despite what some people may say, sabertoothed cats such as Smilodon or Dinofelis (see #4 and #7) were not the ancestors of any modern day cat. They all went extinct without leaving any descendants. However, there may be a potential sabertooth ancestor living today! It is the Clouded leopard, a medium-sized feline from the rain forests of India and southeastern Asia. Just like Dinofelis, the Clouded leopard feeds mostly on primates (monkeys and apes), and is noted for its beautiful fur pattern and incredible agility, but also because it has the longest fangs (relative to body size) of all cats. This is especially evident when you look at a Clouded leopard’s skull. Its fangs are as long as those of many early sabertooth cat species! Scientists claim that the Clouded Leopard could be the beginning of a brand new lineage of sabertoothed cats… assuming of course that this beautiful creature survives long enough, since habitat destruction and poaching are a constant threat over the two Clouded Leopard species living today.