But the story, which played out over months, is usually told in a single sentence. Every detail that led up to the Great Emu War is cut out, and we never hear the answers to those questions that immediately spring to mind: What could have made Australia think going to war with emus was a good idea? And how in the world did they lose? It’s a shame, because the full story is incredible—and a little less absurd than it seems.

10The Emu Were Legitimately Ruining Lives

“Those who didn’t live with the emu couldn’t understand the damage they did,” said Australia’s Minister for Defense, George Pearce. He wasn’t wrong. The emu were ruining lives. The farmers who fought the emu weren’t just ordinary workers. They were veterans of the First World War. When they came home, the government sent more than 5,000 servicemen out to farm Australia’s wild and untamed west. The Emu War is a story of settlers on a wild frontier, fighting against the natives of the land. Who, in this case, just happen to be emus. At first, the farmers were making a profit, until the area was hit by a drought. Starving and desperate, the emus started moving toward the farmlands. They tore holes in the fences, trampled and devoured the crops, and left behind open pathways for the rabbits to get in. Millions of pounds were lost because the havoc these emus were raging. Some farmers gave up and moved back east. Others were threatening to leave. And a few were so driven to despair that they ended their own lives. The emus had to go, and these ex-military men knew one surefire way to do it. Just get us a few machine guns, they told their premier, and they’d clear up the emu problem in no time.

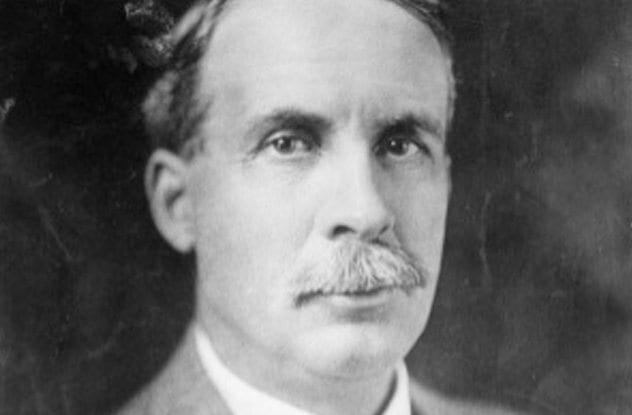

9The Minister For Defense Thought It Would Be Good PR

George Pearce was the man who approved the Great Emu War. He couldn’t put machine guns in civilian hands, of course, but he didn’t see any reason why he couldn’t send a few soldiers out west. So he did it. He had a vested interest in getting rid of the emus. The government had sent these farmers out west, and they needed the crops. But, when they asked Pearce to send them machine guns and military trucks, it was more than just generosity that motivated him. It was the chance for some good PR. Pearce sent a camera crew out with the soldiers to film the Great Emu War. This, he thought, would be his chance to show Australia’s rural voters than he cared. He was going to destroy the emus, save the farmers, and be hailed as a hero. This would be his crowning achievement. Pearce did what he could to make the Emu War his legacy. He justified it as target practice for the soldiers and ordered the men to bring back 100 emu skins and planned to put their feathers in the light horsemen’s hats. He wasn’t completely naive, though. He knew this could go wrong. And he got ready for that backlash. He made the farmers foot the bill and made them sign an agreement with the state. The contract made it clear: if things went south, Pearce wasn’t going to take any responsibility for what happened.

8People In The Cities Were Outraged

The real battle, for the farmers, wouldn’t be against the emus. It would be against the cities. When the people of Australia heard what Pearce was planning on doing, they protested it hard. Senator James Guthrie led the fight against Pearce’s plan, which the press quickly named “The Emu War.” Guthrie said it was “unnecessary cruelty.” If the emu had to go, he argued, then it should be done through “more humane, if less spectacular methods.” Pearce bit back, telling Guthrie, “It is no more cruel to kill the bird with machine-guns than with rifles,” but the cities weren’t convinced. Over the next few days, papers on the east coast were filled with think-pieces calling it “a brutal form of mass slaughter” and rhapsodizing the emu as the great Australian bird. But with or without the support of the cities, the Emu War marched forward. “The farmers would adopt any effective methods to protect their crops,” one paper declared, “and would not ask the permission of anyone before doing so.”

7The Emu Used Advanced Guerrilla Tactics

“The emu,” Sydney’s Sunday Herald warned, “is a tough and unpredictable adversary.” It’s easy to underestimate a dumb, feathery animal. When Major G. P. W. Meredith led the militia west to meet the emu, he was sure it would be an easy fight. They had brought machine guns that fired 300 rounds per minute and more than 10,000 rounds of ammunition. All they had to do, he figured, was point and shoot, and the emu would die. When they launched their first attack, the overconfident militia opened fire from hundreds of yards away. The emu scattered. These animals are incredibly quick, capable of running over 50 kilometers per hour. With every one racing off in a different direction, the militia didn’t have a chance of catching them. “The Emu command had evidently ordered guerrilla tactics,” one writer quipped as the militia ended its first day with nearly nothing to show for their efforts. The militia didn’t totally disagree. The emu, they reported, were smarter than they’d imagine. The animals knew that hunting season had begun, and they were adapting. “Each pack seems to have a leader now,” one soldier reported, “a big black-plumed bird which stands fully six feet high and keep watch while his mates carry out their work of destruction and warns them of our approach.”

6Emus Have The Invulnerability Of Tanks

By Day 2, Major Meredith was taking things more seriously. His militia would no longer just open fire from a distance. This time, they would sneak up on the emu until they were as close as possible before they fired a single bullet. Meredith’s men managed to sneak up on a pack of 1,000 emus, standing only 100 yards away. Then he gave the order to fire. Machine guns blasted at the massive pack of birds, not stopping until they had to reload. But when the dust settled, they’d killed fewer than a dozen emus. “The can face machine-guns with the invulnerability of tanks,” a frustrated Major Meredith reported at the end of the day. The emu’s feathers were so thick that the barrage didn’t even penetrate their skin. “There’s only one way to kill an emu,” one of the soldiers agreed. “Shoot him through the back of the head when his mouth is closed or through the front of his mouth when his mouth is open. That’s how hard it is.” Meredith was dumbstruck. “If we had a military division with the bullet-carrying capacity of these birds,” he said, “it would face any army in the world.”

5The Army Tried To Pick On Easier Emus

After the failure of the second day, Major Meredith and his men fell back. They would give up on the emus they’d been trying to kill and reposition themselves further north, where, he explained, “Emus are reported to be fairly tame.” The first pack they’d fought were just too tough to take down. They were going after an easier target. And this time they were going to run them down with trucks. Major Meredith loaded machine guns up on top of nine trucks and drove after the emus, raining hellfire. It still didn’t work. The emus saw them coming and bolted, usually keeping a good kilometer ahead of Meredith’s men. When they did catch up, it was often even worse. Shortly after, the papers reported on one truck that had accidentally rammed into an emu. “The body became wedged in the steering gear of the truck,” they said, “’which swerved and demolished half a chain of fencing.”

4Bad Press Killed The Operation

As the Emu War stumbled clumsily forward, more and more people were starting to agree that it was a terrible idea. Including George Pearce. The newspapers were reporting that barely any emus had been killed, with some counts as low as 20. The numbers probably weren’t true. Meredith himself claimed they’d taken out 300 emus already. But most people believed the papers. George Pearce’s PR grab had turned into a public embarrassment. On November 8, Pearce gave in. He tried to distance himself from his own decision. He told the press he didn’t want to set a precedent by letting men kill emus with machines guns. The Emu War, by now, was a total joke. When Pearce gave the order, Perth’s Daily News joked, “No treaty of peace has been concluded, and the emus remain in possession of disputed territory.” The militia had barely made a dent in the 10,000 emus that were plaguing the countryside. Now they were going home, and the settlers would be stuck with the bill.

3The Farmers Kept The Fight Alive

Major Meredith didn’t stand down. When Pearce gave the order to come back, he kept fighting. Meredith and two of his gunners stayed out west, patrolling the fence and shooting every emu he saw. The settlers wouldn’t accept it, either. If Pearce wouldn’t support them, they needed a new champion. And they found one in Labor Party Secretary George Lambert. A farmer sent Lambert a telegram. “Gunners withdrawn. Imperative they should stay. Emus beginning to reappear in large numbers,” it read. “Can you do anything?” Lambert was the right man to call. He railed against his fellow politicians for dropping out of the Emu War. And he didn’t mince his words. “It is all very well for the city ‘pussy-foots’ in the House of Representatives to make little of the attempt to eradicated emus with machine guns,” Lambert barked. But the farmers, he told them, didn’t think it was so funny. Major Meredith and the Premier of Western Australia backed Lambert up. The Emu War was working, they insisted, and they were going to keep fighting. Whether the people in the cities liked it or not.

2The Second Emu War Went Better

George Pearce reapproved the Emu War on November 11. “Such strong representations have been made to me,” he announced, “that I have approved of the machine gun party returning to the wheat belt to destroy thousands of emus which are causing tremendous damage to crops.” The Emu War was back on. Meredith and his men learned from their mistakes. On the first day alone, they took out 300 emus, more than they’d killed in their first attempt altogether. As the battle dragged on, the emus grew more careful, but the militia still managed to kill an average of 100 emus per week. The Emu War, now, was going so well that other farmers were begging for militia help. People in other areas soon called George Lambert as well, telling him that they had emu problems of their own and that they wanted Meredith and his men. By the time Meredith turned home, he and his men had killed an estimated 3,500 emus. By then, though, the city papers had run out of emu jokes and lost interest. A single paper reported on the end of the campaign, buried in the “Country News” section. “Farmers now breathe again,” it reported. The emus were too scared to go anywhere near the farms, and the crops were thriving. “Major Meredith and his gun crew,” the paper said, “are to be congratulated.”

1The Farmers Wanted To Do It Again

The emus didn’t stay away forever. Three years later, the country was hit with another drought. The emus came back. The farmers wanted another Emu War, but the government wasn’t about to go down that road again. By now, the story of the war had spread around the world. Australia had been turned into a laughing-stock, and they didn’t want to make it any worse than it already was. Instead, they started a “beak bonus system.” The government put a bounty on every beak torn away from the corpse of a dead emu. It worked much better. In the first two months alone, 13,000 emus died, and, by the end of the first year, 30,000 beaks were claimed. By the ’50s, Australia set up a 135-mile-long “emu-proof fence,” and the days of emu raids came to an end. The farmers in the west, though, didn’t forget the Emu War. Up until the fence was built, they called for militia every time the emus created a problem. To the world, Major Meredith and his men were a joke. But to these farmers, they were the men who had saved their livelihood. Read More: Wordpress