Many familiar forms of life emerged then, but it was also a time of evolutionary experimentation. Weird body shapes and forms developed. Many went extinct. In the Burgess Shale of Canada, their fossils remain. This site is scientifically important not only because of its age but because of the types of organisms fossilized there. Most fossils preserve only the hardest parts of an organism, with the soft tissues being lost. However, the Burgess Shale captured even those most perishable parts of life. The shale formed at the base of an undersea cliff. The sea life was caught and fossilized when mud slid from the cliff above. Here are 10 of the strangest organisms discovered in the shale.

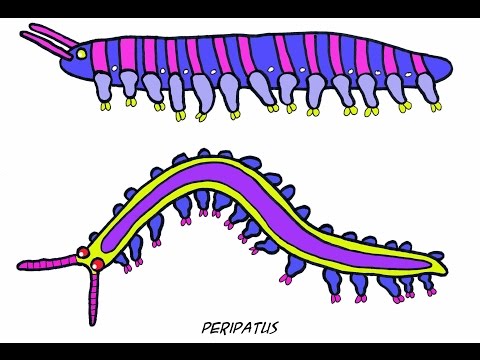

10 Aysheaia

Aysheaia is a small animal with no hard body parts. Without the amazing preserving conditions present in the Burgess Shale, it is unlikely that we would have any fossil record of this amazing animal. Around 5 centimeters (2 in) in length, it had 10 pairs of stubby little legs which bore small spikes. For all its small size, Aysheaia was a hunter. Its fossils are often found beside those of sponges, and it is thought that Aysheaia lived on the sponges and hunted for other animals that also called the sponges home. It may also have been using the sponges for protection. As we shall see, there were larger predators prowling the seas 505 million years ago. This wormlike animal appears to be closely related to a living group of animals. Onychophora (aka velvet worms) today can be found living on land in places scattered across the world. It seems that the descendants of Aysheaia were among the first animals to climb onto the land.[1]

9 Nectocaris

Despite the incredible quality of the Burgess fossils, debates can still swirl around what exactly paleontologists are digging up. A soft-bodied creature buried under tons of mud can be so distorted that its remains have little resemblance to its living form. This is what happened to Nectocaris. The first look at the only Nectocaris fossil convinced scientists that they were viewing a swimming shrimp (which is what its name means). Others thought that Nectocaris might be more closely related to animals with a backbone. Research now points to it being something altogether stranger.[2] The discovery of 91 new fossils of Nectocaris let researchers ascertain that they had found the earliest cephalopod, which is an organism like a squid or octopus. The weird projections at the front of Nectocaris are a pair of tentacles. The head also sported a pair of eyes on stalks. Underneath was a cone-shaped projection which was probably used to give a short burst of speed by propelling water out.

8 Marrella

Marrella splendens is perhaps the most gorgeous organism found in the Burgess Shale. The scientists who named it certainly thought so—splendens is Latin for “beautiful.” Marrella manages to prove that good things come in small packages. This lace crab is only 25 millimeters (1 in) long. The antennae have around 30 segments, and the body has 26. On these complex body parts, large spines were attached. Each body segment has a pair of legs, and each leg has a gill. The animal breathed by kicking its legs. It is believed that Marrella was either a hunter of smaller organisms or fed on organic particles which drifted to the bottom of the sea where it lived.[3] The most striking aspect of Marrella’s shape, the large curved spikes, probably served to protect it from other animals looking for food. It you cannot fit Marrella in your mouth, then you can’t eat it.

7 Canadia

Fossils of Canadia look somewhat like a feather boa has been caught in soggy mud. It turns out that in life, Canadia probably resembled a swimming feather boa. This creature was a small bristled worm around 4 centimeters (1.6 in) long. The length of its body was covered in bristles called setae. These were used to help Canadia swim by acting like paddles as it undulated its body. At the front of the organism are a pair of tentacles that Canadia would have used to explore the world around it. Underneath the head is a proboscis which could be used to take in food. The proboscis was formed from a part of the gut being pushed out of the organism.[4] Canadia may have been a (quite flamboyant) hunter but probably ate both living and dead animals which came between its tentacles. Hidden beneath the bristles are short limbs which would have allowed Canadia to creep over the seabed.

6 Pikaia

Say hello to one of your oldest relatives. Pikaia is one of the earliest organisms that scientists have found with a structure like a backbone. This means that Pikaia, or an organism like it, is probably the ancestor of all chordates (animals with a spine), including fish, reptiles, and mammals. The long, eel-shaped body of Pikaia is crossed with muscular bands, which are another feature of chordates. People often like to boast about their ancestors, but Pikaia is probably not a portrait you would want to hang on your wall. The head has no eyes, merely two tentacle-like structures used for sensing. While Pikaia was probably swimming in the primordial seas, its gut has been found to contain sediment from the organic matter that was available on the seabed. It is possible that all humanity is descended from a bottom-feeding scavenger. How times have changed.[5]

5 Opabinia

When a modern reconstruction of Opabinia was first presented at a scientific conference in 1972, it was greeted with laughter. You can see why. It has five eyes on stubby stalks, a fat, flat head, and a long, mobile proboscis poking out of the front. Due to its bizarre shape, Opabinia had been closely associated with the strange organisms of the Burgess Shale in the public imagination. As it resembled no living creature, scientists found it hard to know where to place it in the tree of life or even guess at how it lived. One idea was that it swam upside down.[6] The proboscis is four times longer than Opabinia’s head and was highly mobile. Fossils of Opabinia have been found with the appendage at many angles and in many shapes. The end is capped with a pair of clawlike fingers covered in spines to allow it to grasp. Many creatures probably looked startled to find their death coming from such an odd animal. Opabinia swam using the fins along its body and grabbed up soft prey with its proboscis before pushing them into its waiting mouth.

4 Wiwaxia

We have seen that the primordial seas were swimming in predators. It’s no wonder that evolution soon developed defensive characteristics to allow animals to avoid being eaten. Wiwaxia looks like a slug, though unlike any that exist today. Debate still rages over whether Wiwaxia is more similar to mollusks or worms, but its life was probably very sluglike. It would have crawled about the bed of the sea scraping its food from the bacterial mats which covered the ocean floor. Wiwaxia had a mouth hidden on its underside, which had a pair of tough plates that could grind up food. Except for the bottom, the body of Wiwaxia was covered in scales and spines. Two rows of spines projected upward from the back. There is no doubt that these were for defense. Their effectiveness can be questioned, though, as many fossils of broken spines and scales have been found. This suggests that predators were able to overcome this deterrent.[7]

3 Ottoia

Ottoia is the most common worm to be found among the Burgess Shale fossils. Studies have linked these creatures to the priapulid worms (aka penis worms). If that is the case, Ottoia is certainly an intimidating member. Ottoia was about 15 centimeters (6 in) long. At one end was a proboscis, covered with 28 rows of hooks, that Ottoia was able to pull back into its body. This was formed from the worm’s gut and used to pull in food. The worms are often found in a U-form, which may suggest the shape they took while hidden in their burrows. Ottoia was carnivorous, however, and so would have come out of its burrow to hunt.[8] One fossil has been found with nine Ottoia feeding on a dead creature. So well-preserved are some of the Ottoia fossils that it is possible to discern what they last ate. One Ottoia has another Ottoia inside it. These creatures, it seems, were cannibals.

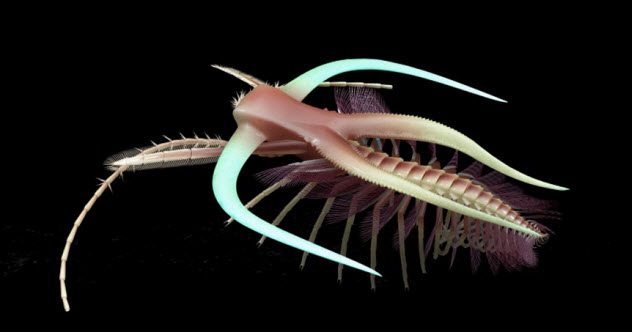

2 Anomalocaris

Scientific progress is not always smooth and easy. Scientists interpret the evidence as best they can. If evidence is fragmentary, then the conclusions reached by scientists can be quite far from the truth. In the end, they get there by reassessing the facts and information they’ve uncovered. Anomalocaris led researchers on a merry dance before they figured out what they had on their hands. The name Anomalocaris means “unlike other shrimp.” It was called this because the first parts found of Anomalocaris were thought to be the rear portions of shrimp. Other parts were thought to be jellyfish. It was only when larger and more complete fossils were uncovered that it was possible to bring the puzzle together. Anomalocaris was the largest predator of its day. A complete fossil has been found that is 25 centimeters (10 in) long, but broken parts of other individuals suggest that it could reach up to 1 meter (3 ft) in length.[9] Its body was suited for freely swimming about in hunt of prey. Those shrimplike fossils turned out to be the grasping appendages on Anomalocaris’s head that captured other organisms. What had been thought to be a jellyfish was actually the creature’s mouth.

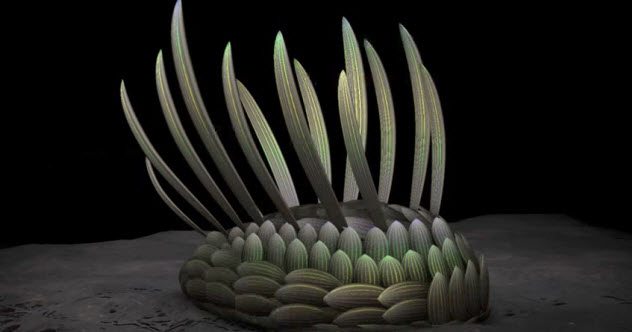

1 Hallucigenia

Few animals have done so much to deserve their name as Hallucigenia. Named for its bizarre body shape, this fossil has puzzled many great paleontologists. The fossils of Hallucigenia show an unidentified thing that is 1 centimeter (0.4 in) long with flexible things on one side and a double row of conical spikes on the other. When first described, it was thought that Hallucigenia walked using those spikes, like a worm on stilts. When the fossils were further explored, it was found that the tentacle-like things on the creature’s back were feet and the “back” of the creature was actually its underside. The spikes were used to protect the tiny organism.[10] A further mystery was only recently solved. Once researchers figured out which way Hallucigenia walked, it remained to be seen which end was its head and which was its tail. What had been thought to be its head, a dark mark on the fossil, was actually a stain left by the creature’s guts being squeezed out after death. The head was found on the other end, complete with a pair of eyes and what looked like a cheeky grin.