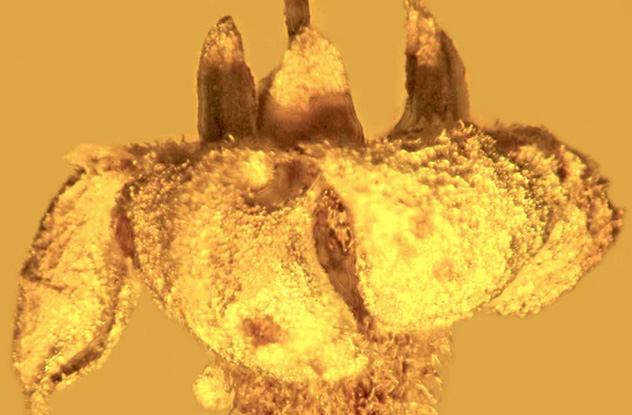

10A Spider With Spikes

Many millions of years ago, spiders were even more terrible than they are today, with large horns sprouting from their carapaces and even fangs. Case in point: Two 99-million-year-old, amber-clad fossils paleontologists acquired from a Burmese dealer. They belong to the extant Tetrablemmidae family, though today’s species aren’t as impressively horned as their ancient counterparts. Like modern Tetrablemmids, the pint-sized prehistoric spiders (one of which is an adorable 1.5 centimeters [0.06 in] long) are decked in armor to repel wasps and other predators. Oddest yet, Cretaceous-era Tetrablemmids also display horned, pronged fangs. But this probably isn’t an offensive adaptation. Rather, it’s probably a sort of speed-dating name tag, allowing males and females to tell each other apart.

9Seabirds With Immense Wingspans

The most inhospitable areas today were once thriving ecosystems, and the Antarctica of 50 million years ago was a balmy, tropical Eden teeming with animal life. But it wasn’t a total paradise. During the Lower Eocene (53–49 million years ago), Cessna-sized seabirds patrolled the Antarctic skies and terrorized ocean life. With plentiful seafood, the sea-going birds achieved horrifying sizes. Recently, paleontologists identified another of these giant avians, several years after recovering its remains from Marambio Island, which crowns the Antarctic Peninsula. The mega-bird and its ilk are known as pelagornithids, or bony-toothed birds. With a 6.4-meter (21 ft) wingspan, the pelagornithid nearly doubles up the largest modern flying bird, the 3.3-meter (11 ft) wing-spanned albatross. In spite of its freakish dimensions, the giant pelagornithid is surprisingly light, weighing in at only 30–35 kilograms (65–75 lb).

8A Turtle Shell Made For Digging

Turtle shells are the most obvious evolutionary design ever. But now researchers argue that shells evolved for burrowing, not protection. The re-think is partially inspired by an eight-year-old South African. Kobus Snyman found a turtle fossil with visible articulations in its hands and feet and ribbed shells—a curious pattern, since the broad ribs aren’t built for strength, like heavy-duty modern shells. The weaker structure suggests an alternate use for history’s first shells, possibly burrowing. In fact, early turtles’ propensity for hiding underground may have spared the species during the Permian-Triassic Extinction that knocked off 90 percent of Earth’s lifeforms.

7One Of The First Flowering Plants Looks Nothing Like A Flower

Although technically we can’t single out a “first flower,” in the same way that we can’t pinpoint a “first human,” according to study co-author David Dilcher, Montsechia vidalii is close enough. Researchers recovered over 1,000 fossilized remains across the Spanish mountains that were once a freshwater habitat. To coax the 170-million-year-old plant from its stony prison, they dabbed the fossils with chemical concoctions to eat away petrified gunk and reveal the outlines of stems, leaves, and even cuticles. Today, montsechia’s descendants are the coontails, or hornworts—the dark green plant that jazz up aquariums and koi ponds. However, their ancestor looked less like a traditional flower and more like salad garnish. Since it spent its entire life beneath the waves, it had no need for vibrant petals or nectar-producing stamens, ovaries, anthers, or pistils that other angiosperms use to lure insects.

6Ancient Insects With DIY Camouflage

Nowadays, some bugs adorn themselves with twigs and organic debris to blend into the surrounding flora. But this trickery traces back to at least the early mid-Cretacious, before flowers burst onto the evolutionary scene during the dull “pre-angiospermous” era. Researchers sorted a massive collection of 300,000 amber fossils collected from around the world, including Burmese, Lebanese, and French varieties. They retained their sanity long enough to identify 35 instances of insect camouflage. Luckily, prehistoric tree resins immortalized these insects pimped out with branches and plant matter. The placement of the debris appears purposeful, suggesting the oldest evidence yet of camouflage. Some of the creepy-crawlies, lacewings and assassin bugs, are lugging around the exoskeletons of various types of lice, which likely served both as a meal and then a disguise.

5 A Raptor With Wings

We know that dinosaurs had feathers, but a northeastern Chinese fossil reveals a raptor with full-on wings, earning Zhenyuanlong suni the coveted title of largest winged dinosaur yet discovered. It roamed Cretaceous forests around 125 million years ago, 40–50 million years before its more popular cousin the velociraptor arrived on the scene. According to paleontologists, the raptor resembled a bird more than anything from Jurassic Park. It might not sound too impressive, but it probably wasn’t too physically dissimilar from modern emus or turkeys. Notable differences include a set of sickle claws and a mouth full of flesh-shredding teeth. And good luck trying to outrun this carnivore, because the feathery dino was probably an accomplished runner. The wings themselves probably looked like fabulously baggy sleeves, comparable to those of eagles or vultures. But they probably weren’t flightworthy, as the raptor’s short arms and unwieldy body were less than aerodynamically ideal. Instead, it might have used its fluffy wings to trap warm air and incubate its eggs. Alternatively, they might have evolved for visual displays, either to woo potential mates or to intimidate rivals.

4Ancient Arthropod Ancestor With Preserved Nervous System

Fresh from a Chinese fossil bed, researchers fished out a 520-million-year-old arthropod ancestor with a clear outline of its nervous system preserved for posterity. Chengjiangocaris kunmingensis was a crustacean-ish animal with a shield-like head, long and possibly slithery body, as well as a multitude of paired legs. It’s a distant relative of spiders, insects, and other exoskeletoned creatures. It lived during the Cambrian explosion, arguably the most exciting evolutionary period in history, which saw an unprecedented and mysterious proliferation of complex life. After clearing away the fossil debris with a needle, researchers discovered a ghostly outline of the creature’s nerve cord, the invertebrate version of a spinal cord. It features numerous bead-like nodes called ganglia spanning its entire length and each control a set of legs.

3Prehistoric Flowers Full Of Strychnine

In prehistoric times, even the plants could kill you. Including one recently identified, thankfully extinct toxic flower that birthed the lethal substances strychnine and curare. In honor of the fossil flower’s amber prison, researchers named it Styrchnos electri, inspired by “elektron,” the Greek word for amber derived from the static electricity generated by rubbing amber with a cloth. Oregon State University professor George Poinar collected the flowers way back in 1986 but put them away with 500 other fossils. He finally examined his finds in 2015 and noticed the potentially interesting plant. The flower was confirmed as a new entry into the genus Strychnos, which comprises 200 known plants that all produce (not always lethal) alkaloids.

2 Lumbering Pre-Dinosaurs That Traveled The Globe

Pareiasaur is an early class of “saur” that predates the better-known dinosaurs by tens of millions of years. Sadly, pareiasaurs didn’t last long and were knocked off after only 10 million years by the end-Permian extinction. At first glance, pareiasaurs look like the dinosaurs’ fat uncle and are therefore occasionally referred to as the “ugliest fossil reptiles.” They needed those large bodies to store their long digestive tracts, a necessity for herbivores that must extract all possible nutrients from roughage. Pareiasaur fossils pop up on most continents, including Asia, Europe, Africa, and South America. But they’re apparently fat and slow, so researchers weren’t sure whether they traveled abroad or simply existed in isolated pareiasaur pockets. Now, science has an answer. Similarities between specimens found in China, Russia, and South Africa suggests they moved all about. And they had a great motive to do so—when you’re Earth’s largest herbivore, the whole world is your salad.

1An Eel-Like Creature With A Pincer For A Mouth

In 1958, researchers poking around an Illinois coal mine fished out a mysterious, fossilized creature that didn’t seem to fit into any known major animal group. The 300-million-year-old fossil sported a toothed pincer for a nose as well as horizontal stalks that held its large eyes, identifying it as a probable predator. In honor of its terrifying appearance, the fossil was nicknamed Tully monster, a slightly less scientific version of its more official moniker, Tullimonstrum gregarium. “Monster hunter” F.W. Holiday even posited that an abnormally large Tully may have inspired the myth of the Loch Ness leviathan. Tully was a vertebrate and the ancient equivalent of the vampiric lamprey, a creature with a similarly elongated, needle-toothed snout used for sopping up blood.

+Antediluvian Groundhog With Surprising Dimensions

As geologic time rolled over from the Mesozoic to the Cenozoic around 66 million years ago, the majority of mammals were small and ratty. But researchers in 2010 discovered a supersized mammal that lived alongside the dinosaurs for a short while. Vintana sertichi is a completely accidental, mammalian-timeline altering find. When Joseph Sertich submitted a fish fossil-encrusted limestone block for review, he had no idea the CT scan would reveal a skull lodged inside. Compared to its shrew-like compatriots, the groundhog-ish animal achieved beast status. Its skull is the largest mammalian cranium recovered from dinosaur-era Gondwana, the southern supercontinent. It’s also the most complete gondwanatherian, shrew-like animals previously identified only by a few teeth and jaw fragments.