10Scrolls For Tortured Souls

Surveyors in the Serbian city of Kostolac have discovered a forgotten burial ground that harkens the former glory of Viminacium, a Roman outpost from the fourth century BC that at its peak boasted 40,000 inhabitants. The site belched up a few 2,000-year-old skeletons and also two mystifying leaden amulets. Inside the amulets, they found adorably tiny scrolls of gold and silver. Commonly referred to as “curse tablets,” such spells generally invoke otherworldly powers to affect or afflict the caster’s friends, family, or foes. The mere presence of magical scrolls suggests the amulet bearers died grisly deaths. Such arcana are buried with the violently murdered, as it’s believed that tortured souls are most likely to encounter the demon middle-men that pass messages on to higher after-worldly offices. Unfortunately, it’s unlikely these particular scrolls will be deciphered anytime soon. Thanks to an inconvenient confluence of culture, the alphabet is Greek but the language is Aramaic, offering a seemingly uncrackable linguistic nut.

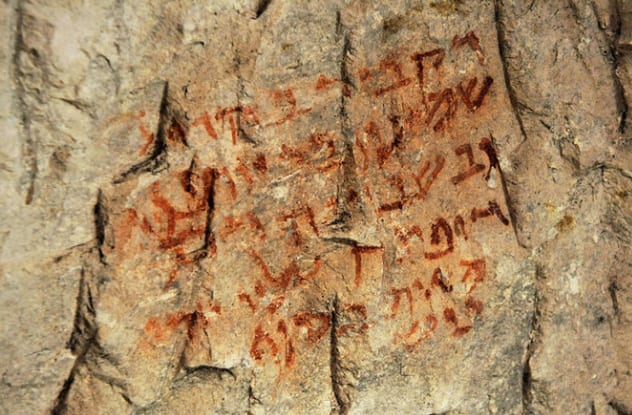

9Galilean Tomb Magic

Tomb robbing has plagued humanity throughout its history of entombing. Hollywood-style booby traps are infeasible, so the denizens of Southern Galilee inscribed curses onto the surfaces at the Beit She’arim necropolis. Dating to the early centuries AD, the catacombs bear markings in a variety of languages, including Greek, Hebrew, Palmyrene, and Aramaic, the universal lingo of the Near East. Roman and pagan influences are present as well, like the sarcophagi that populate a burial trove known as the Cave of Coffins, a practice borrowed from Romans. The messages throughout wish the dead an agreeable resurrection, yet another tradition not inherent to Jewish beliefs. Magical spells in Greek adorn the walls and tombs, preferring protection and peace to the reposed and invoking poxes on any who disturb the sacred bones.

8The Catalhoyuk Statuette

Turkey’s most fruitful Neolithic excavation site is Catalhoyuk, the remains of a settlement established circa 7,500 BC and lasting nearly two millennia before its dissolution. It has relinquished a range of archaeological goodies, from the household to the mystical, including a recently discovered 7-inch, marble statuette of a woman. The first thing you’ll notice is that the Neolithic woman boasts a more substantial figure compared to the female representations of other cultures and times. Similar figurines, though not as large, well-preserved, or delicately crafted, have been found throughout Europe and the Middle East. Researchers previously ascribed them as fertility goddesses, but a new point of view argues a more terrestrial influence. Instead of goddesses of any kind, the sculptures may immortalize the community’s respected, elderly women. The egalitarian community here respected its elders as well as the concept of corpulence, because obesity designated a more distinguished and sedentary clerical or bureaucratic career.

7Re-Used Roman Coffin

In spite of a belief in hexes and pervading fear of sacrilege, coffin recycling was apparently A-OK for Roman Britons, according to a grave site at Dorset Quarry in England. Here, archaeologists discovered an open-faced stone sarcophagus, presenting the skeleton of a man who died mysteriously sometime around 1,500–2,000 years ago. Only 100 or so such burials have popped up across the former Roman Brittania, including 11 others at the quarry, suggesting the individual in question, who died aged 20–30 years old, likely achieved some form of high status to deserve such an unusually dignified send-off. However, this belief is somewhat at odds with the burial itself. The coffin is too small for its 177-centimeter (5’10″) inhabitant, whose feet have been bent back to accommodate the one-size-too-small coffin. Researchers believe the sarcophagus reused like some grisly pass-me-down.

6Moche Ritual Cat Claws

Renowned temple builders and metalworkers, the agriculturally adept Moche populated northern Peru from AD 100–800. Recently, archaeologists discovered a stupefying pair of metal cat claws in a tomb at the former Moche capital. The grave, at the Huaca de la Luna (Temple of the Moon) dig site in Trujillo, also surrendered a man’s body and assorted finery, including a mask, bronze earrings, copper scepter, and mixed ceramics. It’s doubtful that the claws served as weaponry and more likely that they carried mystical value, possibly advertising their owner’s nobility or societal influence. Like their Pan-American neighbors, the Moche enjoyed their own brutal traditions. It’s believed that two warriors squared off in costumed ritual combat, with the winner receiving the costume and claws while the loser earned the privilege of being sacrificed.

5Shamanic Animal Bone Burial

A 12,000-year-old Natufian grave site in Galilee reveals a laborious, six-stage internment process fit for an evil witch. Of the nearly 30 bodies found inside the burial cave near the Hilazon River, one presumably belonged to a female shaman. It was surrounded by an embarrassment of animal parts, including a bovine tailbone, an eagle wing, a pig leg, a leopard pelvis, 86 tortoise shells, deer bones, and a human foot to boot. The burial process began with oval grave and lined with plaster and stone slabs, upon which several different layers of animal parts and flint tools were layered, followed by the woman’s body, then a final garnish of more bones and a triangular stone slab to seal the grave. The process is unexpectedly intricate for the period. Though maybe we should be less surprised, because these same Levant-dwelling Natufians were among history’s first civilizations to ditch the nomadic, hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

4The Vestal Virgin Hairdo

Even more so than today, hairstyles in ancient Rome expressed identity. Personal factors such as age, gender, and station in life dictated one’s hairdo, which doubled as a societal nametag to visually designate one’s role and rank. Most styles are lost forever to history, but at least one has been revived courtesy of self-proclaimed hair-chaeologist Janet Stephens. Inspired by Roman busts in museums, Stephens spent seven years studying a style known as the seni crines, a Roman staple that consisted of six braids. The seni crines was the notorious ‘do that adorned the crowns of Rome’s famed vestal virgins, the celibate devotees of the hearth goddess Vesta, and spiritual tenders of the eternal Roman flame.

3Medusa Good-Luck Charm

The image of Medusa, the serpent-haired Gorgon with a petrifying gaze, is synonymous with evildoing and general villainy. But it wasn’t always so, and some even regarded Medusa as a harbinger of good luck. Like the inhabitants of Antiochia ad Cragum, a first-century Roman city in southern Turkey that hosted the spectrum of Roman conveniences, including an organized, colonnaded street grid, bathhouses, shops, and a rich artistic culture. Within the remnants of the ruined outpost, archaeologists discovered a marble Medusa head. The decoration served as a Pagan apotropaic charm, intended to ward off evil and imbue the settlement with divine protectorship. Myriad similar sculptures adorned the city, though were destroyed by the Christians who smashed a majority of the Pagan iconography to bits.

2Monument To The River God

Ancient life was ruled by a compulsion to appease the gods, who communicated with the mortal world through various mediums. So when the river god Harpasos appeared to Flavius Ouliades in a dream almost 2,000 years ago, it was like a direct message from the heavens. To commemorate the apparition Ouliades erected a marble shrine next to the AkCay River in southeastern Turkey, hoping to invoke Harpasos’s blessing for a fruitful harvest and flood-free season. According to researchers, the scene depicted might portray a particular traditional myth: Hercules’s son, Bargasos, defeating a maleficent river monster in hopes of summoning the riparian deity. Alternatively, the image may pay tribute to divine hero Hercules himself, commemorating his slaying of the many-headed hydra.

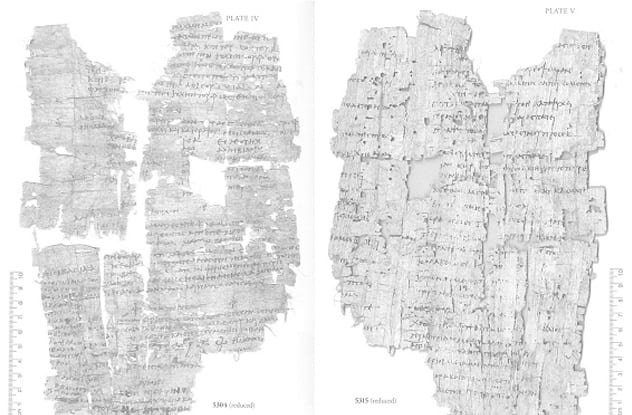

1Egyptian Spells Of Manipulation

The ancient Egyptian arsenal of magic contained invocations for every terrestrial desire, especially in the arena of love. Spells ranged from the hopeful to the overtly evil, as in the case of two recently deciphered papyri from Oxyrhynchus. Written in Greek some 1,800 years ago by an unknown mage, both spells promise varying levels of mind control. One spell claims to subjugate its male victim to the whims of the wielder, while the other spell is female-specific, capable of “burning a woman’s heart” until she falls in love with the caster. The one-size-fits-all spells are open-ended, written to be wielded when and where the occasion strikes. The love-sick caster only needs to insert a name and Bam! Their beloved is now cursed with debilitating fits of passions.