Modern-day rituals are common, and many of these extend far back in history. Examples of these ceremonies, which can include a religious coming-of-age, are a quinceanera, bar or bat mitzvah, First Holy Communion, Rumspringa, bullet ant initiation, sunrise ceremony, or a sweet sixteen. These types of transitional rituals into adulthood were highly prevalent in ancient cultures, too. Here are the traditions that 10 ancient cultures followed to turn their children into adults.

10 Roman Citizens

As teenagers, Roman males would have coming-of-age ceremonies to mark that they had officially become citizens of Rome. The exact timing varied depending on the boy, his father, and the era in which they lived. However, it was usually between the ages of 14 and 17. For the ceremony, the boy would take off his bulla, a necklace that provided protection and was given to the child at birth, and offer it to the Lares (guardian deities). He also stopped wearing a toga with a crimson border, which signified childhood. Instead, he started wearing a pure white toga, just like that of a grown man. Then there would be a large procession to the Forum. There, the boy’s name would be added to the list of citizens. Afterward, the boy and his family would go to the temple of Liber on Capitoline Hill to make an offering before they returned home for a feast. After this, the boy would spend a year with a man chosen by his father. The man would teach the teen how to excel in either army or civic duties.[1] A Roman girl did not have a ceremony signifying her ascent to adulthood. Instead, it was marked by her wedding. This could happen when the girl was as young as 12. She would take off her bulla and give away her toys. Once married, she was officially an adult.

9 Spartan Training

When male Spartans turned seven, they were taken away from their families and moved to the agoge, which was their version of boarding school but with military training and extreme hazing. Their training included physical and mental teachings so that they would become fierce and strong warriors. This period lasted for 13 years. They underwent different tests to see if they were becoming strong and self-reliant. Their last test was the most important coming-of-age ritual—the krypteia. During this year-long test, they had to live by themselves in the wilderness, surviving off the land and killing Helots, the servant class. For this, the teens were not given any weapons or tools and they were not allowed to be seen for the duration of the test. If a teen passed this test, he would become a full-fledged soldier. He would move to the barracks and be on active military duty. He could also marry. If the teen failed the test, he would not be able to join the military ranks. Rather, he was shamed and forced to join the servant ranks.[2]

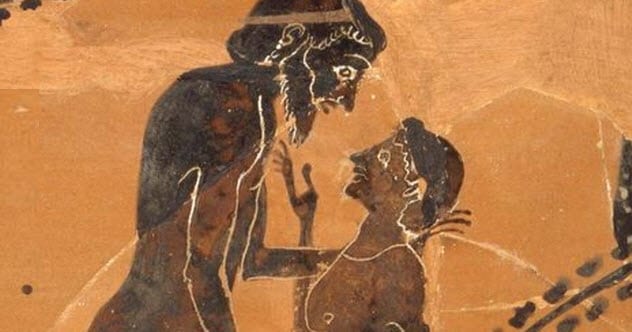

8 Greek Pederasty

Pederasty started in Crete and spread throughout Greece, becoming part of Spartan culture and an important factor in Athenian upbringing. It was the practice of an older male courting a pubescent boy. The older man would woo the boy with gifts until the boy accepted or rejected the adult (thus choosing to wait for another). If the man was accepted, they would enter into a sexual relationship in which the older man was always dominant and the boy was submissive. During this time, the older man was supposed to teach the boy important things for later life and adulthood. The man was a teacher, a protector, and a model for virtuous behavior. Once the boy was considered mature enough, the relationship would end. He could then take on his own submissive boy if he chose. In modern society, this sounds highly immoral and sexually abusive, but the Greeks considered it a normal part of a boy’s upbringing. This stage was an important part in the transition from childhood to adulthood.[3]

7 Yucatec Clothing

In different Mesoamerican cultures, the appearance of a child or teenager would indicate which stage of life they were in. Changing this appearance was part of a ritual performed as a person entered a new phase in life. Yucatec children did not wear clothes until they turned five. At this point, the boys would don loincloths similar to those of their fathers and the girls would start wearing skirts like their mothers. Each boy would also get a white bead to tie in his hair, while each girl got a string with a red shell on it to wear around her waist.[4] These symbols of childhood were worn until they were taken off in a ritual ceremony that signified that the children had started puberty. They were not allowed to marry until they had passed through this ceremony and discarded the indicators of their youth. As the parents decided when their children could marry, the youngsters would sometimes go through the ceremony before they had reached puberty. The ceremony was conducted for a group of kids close in age rather than for one individual at a time.

6 Mexica Appearance

Markers of age were more permanent among the Mexica (aka Aztecs). Mexica girls would receive marks through scarification on one hip and breast to show that they could start school. Meanwhile, boys got lip plugs for the same stage. They received these rites of passage in a ceremony where they were taught how to behave and what their families would expect from them in their new chapter in life. The children would stay in their new school until they married, which was symbolic of their transition from childhood to adulthood. Hairstyles were also significant among Mexica boys. As kids, they had shaved heads. When they turned 10, they could grow out their hair and essentially have man buns. Most boys would catch their first enemy warrior when they were about 15. They would then cut their hair so that it was only long over the right ear. This would signify their approach to adulthood. However, they still had to capture another enemy. Until then, they had to keep their hair long on one side, which was a female hairstyle.[5]

5 Inca Puberty Rituals

For the Inca, a girl became a woman once she had her first period. When this happened, the girl would stay inside her house without eating. On the third day, she was given some corn and her mother bathed her, braided her hair, and gave her new, clean clothes. Her relatives would visit, and she would exit the house to serve them food and drinks. This was an important ceremony where her closest uncle would give her a new, permanent name and her other relatives would give her gifts. For noble boys in Cuzco, there was a transition ceremony in the December of their fourteenth year. Before the ceremony, they would make a pilgrimage up Huanacauri, a mountain southeast of Cuzco, to sacrifice a llama. A priest would smear the animal’s blood on the boy’s forehead, and he was given a sling to signify that he was a warrior. This was followed by a period of dancing, more pilgrimages, and more llama sacrifices.[6] On one of the hikes, the closest uncle would give the boy a sling, a shield, and a mace. His legs would also be whipped to toughen them up. In the last ritual, he would get one ear pierced so that he could wear the plugs that signified his noble status.

4 Aboriginal Walkabout

Historically, the Australian Aboriginal ritual of a walkabout, or temporal mobility, was performed by teenagers as their initiation into adulthood. This usually happened when an individual was 10–16 years old, though the elders of the tribe decided when a child was ready for it. Prior to the walkabout, the elders would teach the child all about adulthood, how to survive in the wild, and how to perform the ritual. The walkabout itself would last for around six months, and the child sometimes walked up to 1,600 kilometers (1,000 mi). During this period, the child was expected to survive in the wilderness on his own without interacting with another human. This would prove that he could live off the land and be self-reliant as he would have to make his own shelter and find his own food and water. The child would leave his tribe wearing nothing but a loincloth, though his body was likely decorated with paint and ornaments. Some tribes would remove one of the child’s teeth or pierce his nose or ears. This ritual was not only a test of survival skills. The child was also meant to discover himself and communicate with his spiritual guides. As he was walking, he would sing ancient songs that were used to guide him through the land. These songs were called “songlines,” and their use was believed to invoke the help of spirits. Once the child successfully returned to his tribe, he was considered an adult.[7] People still go on walkabouts today, though it’s more of a self-discovery act rather than a transition into adulthood. Rather than sending out children, adults go on these journeys.

3 Chinese Capping Or Hairpin Ceremony

In China, a tradition from the Zhou dynasty turned boys into men through a capping ceremony and girls into women during a hairpin ceremony. Males went through the ceremony during February when they were 20. They chose an honored guest who would roll their hair into a bun and put a cap on their head during the ceremony. The two of them and the host, who was usually the father, would wear ceremonial clothing for three days before the ceremony. After the honored guest had fixed the boy’s hair, the guest would give a speech wishing the boy good luck in his future and telling him that he was an adult now. The boy then bowed to his mother before the honored guest gave him a new name.[8] For a female, the ceremony happened between her engagement and wedding, though it could happen no later than age 20. It was a similar procedure, though someone would roll her hair into a bun and fasten it with a hairpin rather than give her a cap. The ceremony also included mostly women and was held in her home.

2 Viking Men

To be considered men in Viking society, boys had to prove themselves. But they didn’t have a set ritual that everyone followed. Legally, boys were considered men once they turned 12. At this age, they could marry. However, in many places, boys were not deemed to be men until they had lived through 15 winters. In Iceland, a boy had to prove that he could ride a horse properly and was able to drink with men. As all the kids had to help out on farms, some places didn’t consider boys to be men until they had learned to accomplish all the tasks needed to run a farm. Once they proved that they could be completely self-reliant and did not need their families anymore, they were men. This included being a successful hunter and warrior as well.[9] Specifics about how a female passed into adulthood are scarce, but girls were often married as young as 12. Thus, the wedding was most likely the main transition ceremony turning a girl into a woman.

1 Celtic Quest

Among the Celts, at least the Irish Celts, the coming-of-age ritual was very important for boys. It was a highly religious event that was supposed to turn a boy into a warrior and, subsequently, a man. The ritual consisted of a quest, though the nature of it differed depending on the tribe. Some boys were sent out into the forest on a scavenger hunt. They had to come back with certain items to show that they were self-reliant and capable. Others had to head far into the wilderness on longer expeditions. This would show how well they could take care of themselves. To manage this, the Celts believed that the boy would be able to evoke help from a god or goddess, an important part of transitioning into an adult. Sometimes, girls would also undertake this quest, though it was not as necessary for them as it was for boys.[10]