Each of these ten early films of turn-of-the-century (the 20th century, that is) celebrities brings history to life as it shares glimpses of a famous man or woman who contributed greatly to our own time and lives.

10 Anne Sullivan and Helen Keller

In a sequence from a 1930 newsreel film, now on video, Anne Sullivan (1886-1936) explains how she taught Helen Keller (1880-1968) to speak. Keller, who is also present in the film, demonstrates. Her student, Sullivan says, had been blind, deaf, and mute since she was nineteen months old. It was a mystery to Keller how Sullivan and others managed to speak without using their hands, as she herself must do. By teaching Keller to place her hand over Sullivan’s face, the teacher showed her student “how we talk with our mouths,” letting Keller feel the vibrations of the spoken word. In response, Keller immediately spelled the message, “I want to speak with my mouth.” With her thumb on Sullivan’s larynx, her forefinger on her teacher’s lips, and her third finger alongside Sullivan’s nose, Keller could discern the various vibrations of sounds—those of the hard “G” and the “K” on her thumb; the “V” and the “T” sounds on her forefinger; and the nasal sounds, such as “M,” on the third finger on Sullivan’s nose. The first word she learned to speak was “it.” After seven lessons, Keller was able to articulate the sentence, “I am not dumb now,” as she does in the video footage while smiling in delight.[1]

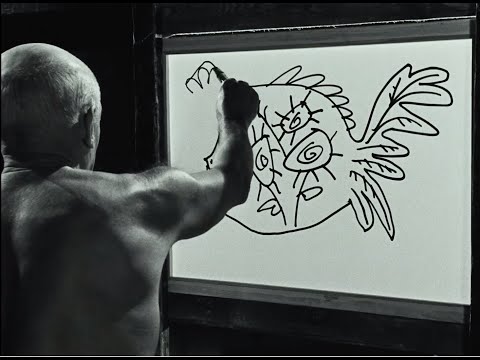

9 Pablo Picasso

In an excerpt from French filmmaker Henri-George Clouzot’s documentary Le Mystere Picasso (The Mystery of Picasso), Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) draws a picture for the camera filming him. The video, posted by the Royal Academy of Arts, begins with an image of Picasso’s finished painting Visage: Head of a Faun before showing him actually creating it in 1955. Stop-action and time-lapse photographic techniques allow Clouzot to capture the artist’s process as Picasso begins drawing with a black marker and the resulting images bleed through the paper. As he works, Picasso’s drawing undergoes a series of spontaneous metamorphoses, “from flower to fish, to chicken, to face.” Dark, heavy lines are introduced over and among the finer lines he has already committed to the paper. Picasso looks intent as he begins to paint around the drawing, filling in the negative space with dark blue and using thick strokes of green paint to outline the face on the side of the flower-fish-chicken’s body. At this point, Clouzot, consulting his wristwatch, advises, “45 seconds left” of the five minutes total that are represented by the 450 feet of film being shot. Time enough remains to add some red to the hybrid face’s nose (which doubles as the hybrid creature’s wing), its leafy branch of a tail, its eyes, and its leaf-like wattles. The filmmaker cheats, allowing Picasso a bit more time than the original five-minute limit. The artist colors the ground red. “8 seconds,” Clouzot announces, and Picasso brushes black over most of the strange creature before creating a trio of twig-like human figures that seem to “grow” out of the earth. Then, the filmmaker orders his camera operator to quit filming. Fifty-five years later, the video announces that Picasso’s painting is “restored” for a Picasso and Paper exhibition.[]

8 Albert Einstein

Although Albert Einstein’s (1879-1955) famous equation E=mc2 is well-known throughout the world today, it was revolutionary when he first articulated the idea that energy and matter are interchangeable. To hear Einstein himself state the implications of his famous equation is, nevertheless, impressive. Initially, the video showing the mathematician’s explanation appeared in 2011, many years after formulating it in 1905. Apparently reading from notes, he states that “it followed from the special theory of relativity that mass and energy are both, but different, manifestations of the same thing.” He adds that such a notion is apt to be “a somewhat unfamiliar conception for the average mind.” Then, presumably to help his audience grasp the significance of the equation, he defines its terms—E, M, and C squared (energy, mass, and the velocity of light squared, respectively). He does this before explaining that “a very small amount of mass may be converted into a very large amount of energy, and vice versa,” since the two are, in fact, equivalent. For those of average mind who may be skeptical of his explanation, he tells listeners, with just a hint of a smile, that the equivalency of mass and energy was demonstrated by John Douglas Cockroft and Ernest Thomas Sinton Walton in their 1932 experiment.[3]

7 Mata Hari

According to the History website, after her marriage, plagued by infidelity and domestic violence, crumbled in divorce, her son’s death, and losing custody of her daughter, Margaretha Zelle (1876-1917) moved to Paris. She was seeking to reinvent herself so she could “live like a colorful butterfly in the sun.” Incorporating moves she’d observed during her time in the Dutch East Indies, she created a Hindu dance act, appearing first as Lady Gresha McLeod and then as Mata Hari or “eye of the day.” Realizing that she lacked dance skills sufficient to draw a crowd, she compensated by casting off items of her colorful costume until, at the conclusion of her dance, she was nearly nude. “People came to see me because I was the first who dared to show myself naked to the public,” she said. The details of Mata Hari’s espionage career remain sketchy. However, it seems to have begun [if, indeed, it began at all] in the fall of 1915, when she allegedly accepted honorary German consul Karl Kroemer’s offer of money to spy for the Kaiser under the “German codename” H 21. On February 13, 1917, she was placed under arrest, charged with espionage, and confined to Paris’s infamous Saint-Lazare prison, where she was interrogated. Although she admitted to being a courtesan, she denied ever having spied. Despite the flimsy circumstantial evidence, she was convicted, and on October 15, 1917, she was executed by a firing squad at age 41. The footage of Mata Hari humanizes the exotic dancer. Despite her later admission of having been a prostitute, her work as an exotic dancer, and her conviction for spying for Germany during World War I, she appears, in this earlier video, as simply a well-dressed, beautiful young lady. Wearing a long, pleated dress with a large hat, stockings, and high heels, she is helped into her long winter coat by a soldier who then helps her into the back seat of an automobile that has arrived to collect her. Perhaps the soldiers in the front seat are taking her to “the spy school” the video’s narrator mentions her having to attend as a condition for receiving the funds she needs to return to Paris.[4]

6 Marie Curie

Marie Curie’s celebrated career and award-winning accomplishments are summarized by The Nobel Prize website. In her youth, Marie Curie, then Maria Sklodowska (1867-1934), of Warsaw, Poland, was trained by her father in scientific study in addition to her general education before moving to Paris after involving herself in “a students’ revolutionary organization.” Finding it prudent to leave the city, she continued her education at the Sorbonne, where she met Professor Pierre Curie. They married a year later, in 1895. She earned her Doctor of Science degree in 1903 and, working with her husband, isolated both polonium, named after the country of Marie’s birth, and radium. She also encouraged using radium as a medical treatment for alleviating suffering. During World War I, she remained focused on this work with the help of her daughter, Irene. In addition, a Nobel laureate twice over, Madame Curie, as she was also known, served as a member, a professor, or a director of various professional and scientific organizations throughout her career. Despite both her many accomplishments and the fact that she was held in high esteem and admiration by scientists throughout the world, she remained, as The Nobel Prize website describes her, a “quiet, dignified and unassuming” woman throughout her career. Her reserve and modest demeanor are on display in the video conversion of the 1931 Pathe News filmstrip showing her gracious receipt of yet another award bestowed upon her, the ARC Gold Medal. After the presentation, she addresses the world, wearing her hat, large round glasses, a dark dress, and her latest award: “I would like to express here all my thanks to the delegation of the American College of Radiology for the honor that brings me here and by which I am extremely touched.”[5]

5 Annie Oakley

Annie Oakley (1860-1926), an expert shot with both pistols and rifles, was as popular, perhaps, for besting male competitors as she was for her unerring accuracy. She defeated all contenders, including her future husband Frank E. Butler. He missed one out of twenty-five shots in a contest, while Oakley’s aim proved faultless. She had had lots of practice in perfecting her aim, as she had begun hunting game at age eight, supplying it to local restaurants to help put food on her family’s table. Impressed by her accuracy, General George Armstrong Custer dubbed her “Little Sure Shot,” which became her Wild West Show stage name. One of her career’s highlights was her performance before Queen Victoria at Her Majesty’s Golden Jubilee in England. However, her travels in Buffalo Bill’s show included Spain, Italy, and France. Her good name was impugned when a false story began circulating after she’d injured her back in a train wreck in 1901. As many as fifty-five newspapers claimed that she had stolen a man’s trousers so she could sell them and use her ill-gotten gains to purchase cocaine. This feat proved impossible since the crime had occurred in Chicago while Oakley and her husband resided in New Jersey. The reports turned out to be true in this regard: Maude Fontanella, the thief who had stolen the man’s trousers, had gone by the false name “Any Oakley.” Incensed at the newspapers for falsely accusing her, Oakley sued and won 54 out of 55 cases against the newspapers. Her expertise with guns is put on display in a remarkable U. S. Library of Congress video that shows her shooting disc-shaped targets attached to a standing board and coins tossed into the air. Although she appears to miss one of the seven discs, which remains on the board after the other six fall, a careful review of the action shows that she did, indeed, strike the seventh disc, too—at dead center, in fact.[6]

4 Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

In his own words, as we look on during a 1929 interview, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) shares what inspired him to write detective stories featuring a consultant who uses science instead of luck to solve the mysteries he investigates. Then, ironically, he fills us in on his psychic experiences and interest in the spirit world. He was annoyed, Doyle says, at how, “in the old-fashioned detective story,” the detective seemed to succeed either as the result of “some sort of lucky chance or fluke” or never explained the process by which he reached his solution. Doyle found this state of affairs unfair, believing the detective should have explained his methods. As a result, he decided that scientific methods should be applied to crime detection. Recalling the method that Professor Bell, one of his college teachers, used to diagnose diseases in his patients, Doyle decided to write detective stories of his own in which his detective would use methods similar to those Bell had employed. Once his readers caught on to the fact that Doyle’s stories delivered something new to the genre, his narratives of Sherlock Holmes became increasingly popular. Doyle then turns his attention to the much more serious topic of his interest in spiritualism. His study developed “about the year[s] 1886 and 1887.” In the forty-one years between then and now, his interest became ever more profound as he read about and studied psychic matters and experimented with them. Slowly and carefully, he formed his convictions about the subject. Since then, he had taken it upon himself to educate the public about the great philosophy, the truth of which he has observed firsthand at seances and in other situations all around the world. He assures us, “I am not talking about what I believe. I am not talking about what I think. I am talking about what I know.” His devotion to spiritualism, he asserts, had comforted him, even as it had helped him, especially during the aftermath of World War I, to console many people who lost loved ones.[7]

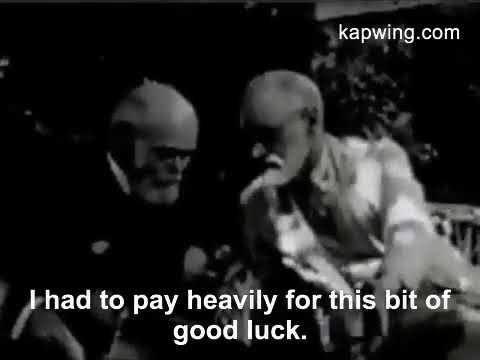

3 Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) reminds his audience that psychoanalysis has made much headway but is far from being universally accepted. In this film, we hear Freud’s voice over a series of film clips. The recording briefs us on the state of the psychoanalytic school of psychology he founded. It comes from a BBC radio interview conducted at his home at Hampstead, North London, on December 7, 1938. It is believed that this is the only known audio recording of Sigmund Freud. Freud is a little hard to understand in this interview as he was suffering from incurable jaw cancer and every word was agony. After briefly recounting the general principles of psychoanalysis, Freud gets personal, declaring, “I had to pay heavily for this bit of good luck” in discovering these findings and pointing out the intense opposition he faced by “people [who] did not believe in my facts and thought my theories unsavory.” Despite such opposition, he declares, he “succeeded in acquiring pupils and building up an International Psychoanalytic Association.” Strangely, almost as if he’s inviting his listeners to continue the good fight he has begun, he concludes, “But the struggle is not yet over.”[8]

2 Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (1835-1910), better known to the world by his pen name Mark Twain, appears in a silent bit of footage taken at Stormfield, his Redding, Connecticut, home. The mansion was named for his iconoclastic 1907 short story “Captain Stormfield’s Visit to Heaven,” the profits from which helped fund the house’s construction. The video begins with an announcement: “This is the only known motion picture of Mark Twain. Photographed in 1909 using Thomas Edison’s Kinetograph camera, it also shows what is believed to be his daughters Clara and Jean.” After greeting us, he strolls along his driveway, coat open, vest buttoned, smoking a cigar on a breezy day. The scene shifts and he is seated at an outdoor table with his daughters, with whom he drinks tea as they appear to engage in conversation. Unfortunately, the film is unaccompanied by sound. The clip may not be much to look at by today’s standards. However, the simple fact that it provides a glimpse into the life of one of America’s greatest writers, allowing us to see the man behind literary works that have stood the test of time, makes it impressive, nevertheless.[9]

1 Queen Victoria

As we watch a rare bit of film that was converted to video, we may feel that we are part of the crowd who assembled to greet Queen Victoria (1819-1901). The footage was shot during the queen’s last visit to Ireland in 1900 and shows Her Majesty in a horse-drawn carriage as she nods at a crowd of well-wishers lining both sides of the street down which she rides. Wearing sunglasses and holding a parasol, she nods and smiles, her carriage pausing so her attendants may accept a huge basket of flowers from a pair of curtseying ladies in white dresses and hats. As a commentator points out, by seeing the queen, the embodiment of the British Empire, in action, “moving [and] alive in the middle of a scene [viewers] get a sense of being in the same world with her” as they make “an immediate connection” and she reveals her personality. New York City’s Museum of Modern Art acquired “thirty-six reels of nitrate prints and negatives made in cinema’s first years,” which were restored. Among the footage is this amazing sequence of film.[10]