As a sort of bitter joke, we can look to some of the other creatures on Earth and find that they have what we wish for. Some refer to these animals, perhaps mistakenly, as biologically immortal. But they can die. The difference is in how they arrive there—without ever growing old as we do. Rather, they keep their youthful vigor right up until some other means takes them. Here are 10 animals that do not die of old age or can halt the process.

10 Marine Sponges

As far as multicellular animals go, marine sponges are as simple as they come. They don’t possess the common elements that other animals (like us) have in abundance. They have no internal organs, digestive tracts, or nervous and muscular systems. Yet a marine sponge specimen has been found to be at least 11,000 years old, with some studies suggesting the potential life span of these creatures to be in the hundreds of thousands of years. The key to their longevity may lie in their simplicity. Andrey Lavrov and Igor Kosevich, biologists who studied marine sponges’ abilities, found that when the sponges were subjected to tissue dissociation (by mechanically or chemically separating the cells from one another), the sponges were able to re-form into their original shape. The biologists reported, “In a number of cases, such multicellular aggregates may result in a full reconstruction of an animal’s initial organization.” These amazing regenerative abilities render these creatures nearly ageless.[1]

9 Planaria (Flatworm)

Our school classes taught us about the special regenerative powers of the flatworms, unassuming creatures that harbor the ability to regrow into two healthy flatworms if cut in half. Recently, a lab at MIT performed an experiment that regrew an entire flatworm from a single cell. But one cause of this remarkable feat may not have been mentioned in our high school classes. Dr. Aziz Aboobaker of The University of Nottingham commented: Usually when stem cells divide—to heal wounds or during reproduction or for growth—they start to show signs of aging. This means that the stem cells are no longer able to divide and so become less able to replace exhausted specialized cells in the tissues of our bodies. [ . . . ] Planarian worms and their stem cells are somehow able to avoid the aging process and to keep their cells dividing. Due to this cellular youth, flatworms defy aging, making it difficult to accurately measure a flatworm’s life span.[2]

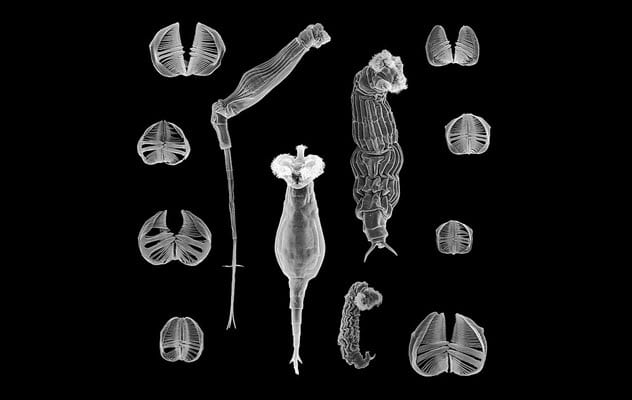

8 Bdelloid Rotifers

These small—1 millimeter (0.04 in) or less—creatures can be found the world over in any body of water but also in such homes as mosses and lichen. In general, they live for about 30 days. Hardly ageless, so why their place on our list? These microscopic animals have a powerful ability to stop their bodily functions in times of crisis, such as starvation or dehydration, and suspend their own aging process. In fact, this prolonged time of inactivity can be longer then their normal life span. Some bdelloid rotifers could last 40 days while starving and then pick up again with their normal life spans as if the 40-day period had never happened. This would be like finding humans who could go without eating for 100 years without aging a day the entire time. Once food was available again, they would pick up aging where they left off and live a normal life from then on.[3]

7 Hydra

This creature is only about 2.5 centimeters (1 in) high and treelike. To understand its place on our list, we need to understand the concept of senescence, which is the increase in mortality rate as a creature gets older. For example, humans are more likely to die the older we get. However, the Hydra does not have this increase in mortality. (Except for one species, Hydra oligactis. Sorry, buddy.) They accomplish this feat using three distinct types of stem cells, which are initially undifferentiated and can eventually become many different specialized cell types. These stem cells are actively renewing the body of the Hydra and thus fighting off any aging process that could lower their mortality rate. In a laboratory setting, it’s estimated that 5 percent of Hydra could live up to 1,400 years using this process.[4]

6 Ocean Quahog Clam

This marine bivalve mollusk is special because it is exceptionally easy to determine the creature’s age. Like a tree, its life span is recorded in the growth rings of its shell. Even more, those rings offer insight into its life—with wide rings showing a year of plentiful food and narrow rings showing a scarcer time. Due to this trait, one ocean quahog was dated to 507 years old—the oldest of its kind ever found. This would put its original birthday sometime in 1499. The secret to this longevity is linked to the quahog’s unusually thin production of reactive oxygen species, which are unstable and oxygen-holding molecules (aka free radicals). Buildup of these molecules can cause damage to DNA, RNA, and proteins and result in cell death. Due to the quahog’s attenuated amount of these reactive oxygen species, it is able to fight off a common source of aging and live for many centuries. The 507-year-old quahog, named Ming, only met its end because it was frozen after its capture to allow researchers to properly determine its age. In all likelihood, it could have lived for much longer.[5]

5 Lobster

Often caught to be eaten as delicacies, these bottom-feeding ocean animals have indeterminate growth, which means they have no maximum size. As a result, the longer a lobster lives, the bigger it will get—with no biological process to halt that growth. The heaviest lobster ever caught was a little over 20 kilograms (44 lb). It was found off the coast of Nova Scotia. Estimates of these animals’ life span range from 50 to 100 years—not much different from that of humans. But the fascinating thing about lobsters is how they age and die. They show no loss of appetite, sex drive, energy, or metabolism as they get older. However, lobsters do make it hard to measure their age. They grow in a process of molting, where they shed their entire exoskeleton. After each molting, all hard surfaces of the animal are discarded. So there is nothing left that can be aged with accuracy. It is that process of molting that eventually kills them and not the usual aging process that humans face. The larger a lobster becomes, the more dangerous molting is and the more energy it takes.[6] Eventually, a large lobster will no longer be able to survive the process or even muster up enough energy to begin it, thanks to its giant size. If this hurdle were somehow removed, there’s no telling how long these creatures could live.

4 Midland Painted Turtle

Although many turtles show a long life span and lack of senescence, Blanding’s turtles and midland painted turtles have a seemingly backward take on aging. The elderly females lay even more eggs than their younger counterparts and die at a lower rate. They become more likely to keep living with age. The longevity of the entire turtle family is impressive. One giant tortoise lived to at least 250 in the Calcutta zoo. Dr. Christopher J. Raxworthy from the American Museum of Natural History said plainly, “Turtles don’t really die of old age.” Instead, the internal organs of elderly turtles are almost identical to those of their teenage counterparts.[7] This impressive life span is also shown in how slowly female turtles reach sexual maturity—only after 40 or 50 years in some species. Dr. Raxworthy added that if it weren’t for getting crushed by an automobile or falling prey to a disease, a turtle could live indefinitely.

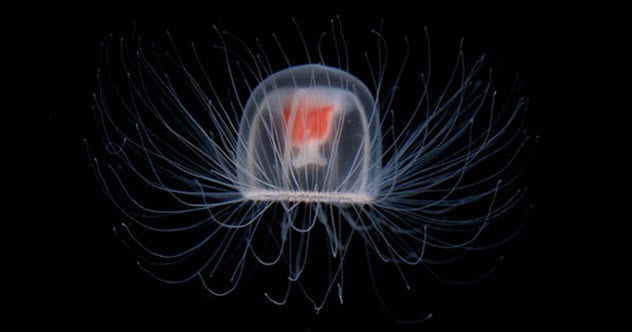

3 Turritopsis Dohrnii (Jellyfish)

Imagine that we could decide on a whim to reverse our aging at any point in our lives. Our hair would get less gray, our wrinkles would disappear, our bodies would get stronger, and our metabolism would increase. We’d be like teenagers again and then like children and, finally, like babies. Then we’d start aging again from the beginning, living our lives a second time none the worse for wear. This is the exact situation of the Turritopsis dohrnii, the immortal jellyfish. At any point in its life, the jellyfish can reverse aging in a process known as transdifferentiation, revert to its earliest form, and then continue living from there. So far as we know, this process can continue without end. This mechanism can be triggered by anything from mutilation to old age, starvation, or disease. If left to their own devices, these jellyfish will rejuvenate about 10 times over the course of two years. Sometimes, these events happen less than a month apart. Also a proficient hitchhiker, this everlasting jellyfish has spread to every ocean in the world by hitching rides on cargo boats.[8]

2 Bristlecone Pine Trees

These gnarly and knotted trees look anything but ageless. Their lifetime seems evident in their shape, with branches twisting in and around on themselves like the bony fingers of an old man. Inside, though, is a life-form of incredible sturdiness. The bristlecone pine measures its life not in centuries but in millennia. The oldest one discovered is estimated to be over 5,000 years old. The exact location of this tree and other exceptionally old bristlecone pines is kept a secret to keep them safe from intentional or accidental damage. Dated to be just under 5,000 years old, another bristlecone pine named Prometheus was cut down in the same area. This pine’s wood is dense and resinous, giving it natural defenses against threats like fungi and insects. Even if the tree does die, its dead form holds on strong for centuries and is kept upright by its roots.[9]

1 Pando Tree Colony

Its name means “I spread” in Latin, and it’s also known as “the trembling giant.” This massive organism defies all expectations. It is a grove of quaking aspens, named for the sound the leaves make at even the slightest flutter of wind. Pando is a colony of trees spread across 100 acres of land, and every tree there is the same organism. This is because quaking aspen trees reproduce mainly by sprouting new trees from an already existing root system. A single organism can have many tree trunks sprouting out of the ground. Pando has 47,000 trunks. The individual trunks only persist for 100 to 150 years or so, but Pando as a whole has been estimated to be at least 80,000 years old with optimistic estimates at one million years old. This everlasting grove is among the oldest and largest living creatures on our planet and weighs some 6 million kilograms (13 million lb).[10]